Zombie FCC vs. Schoolhouse-Rock Supreme Court

Heavy-handed Internet regulation is back . . . for some reason. But don’t expect it to last.

The Biden administration needed more than two-and-a-half years to seat a full slate of Democratic commissioners at the Federal Communications Commission. At last they have their 3-2 majority, and they can get back to trying to strangle the Internet.

There are two big items on the agency’s agenda, and I’ve published an article in City Journal on each of them.

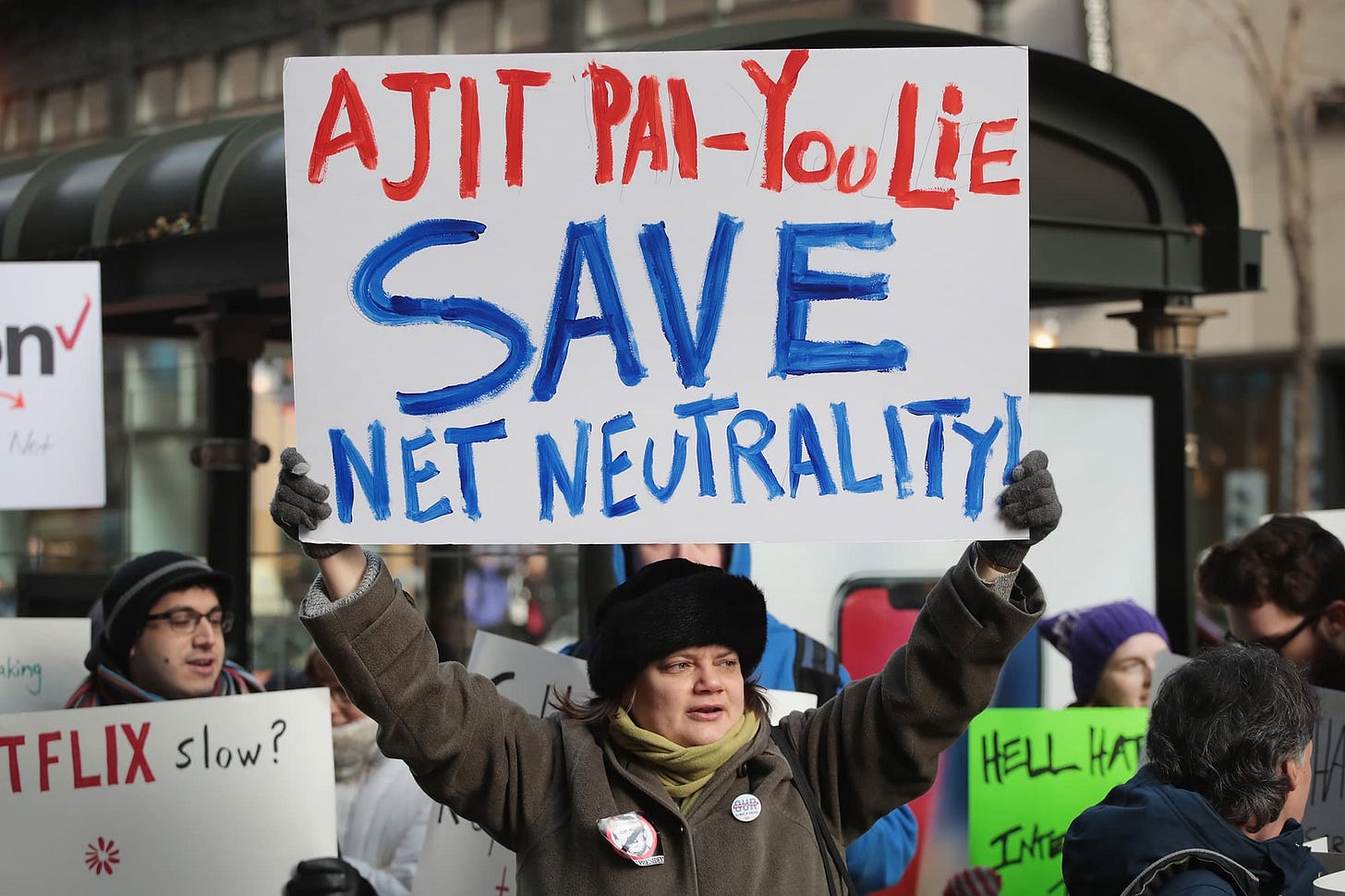

1. Last month, the FCC renewed its push for “net neutrality” rules. It’s a lousy label, since “neutrality” is only a small piece of the agency’s plan. The idea is not simply to ban blocking or throttling—barring or slowing access to content for reasons of greed or ideology—but to impose utility-style regulation. The new rules would empower the agency to wipe out certain data plans, police rates for “reasonableness,” and enforce a vague but pervasive “general conduct standard” for how broadband is served to customers.

This is a tired debate—Democrats have forgotten why they wanted net neutrality in the first place—but the new proposal is no less pernicious for that. Fortunately, its chance of survival is slim. So I contend in City Journal article number one, “A Thankfully Doomed Mistake”—out today. I throw the new net neutrality plan into the Supreme Court’s “major questions” woodchipper, with predictable results.

“Recently,” I note:

the Supreme Court has been sharpening its major-questions rule. In a system of government of, by, and for the people, this rule should pass for common sense. The major-questions rule assumes that Congress, the nation’s highest lawmaking body, does not lightly relinquish its authority to make law. . . .

In West Virginia v. EPA (2022), the Court announced the “arrival of the ‘major questions doctrine.’” That, at any rate, is how the dissent put it. More accurately, the Court used the “major-questions” label for the first time, in a decision that streamlined various rulings deploying the underlying principle. The major-questions rule stands on a presumption, the Court said, quoting [an opinion written in 2017 by then-judge Kavanaugh], “that Congress intends to make major policy decisions itself, not leave those decisions to agencies.”

The major-questions rule says that an agency can “make major policy decisions itself” only when Congress has clearly authorized it to do so. Over the last two years, the Court has applied the rule several times, i.e.,

while striking down the Centers for Disease Control’s push to restrict evictions during the Covid-19 pandemic (Alabama Association of Realtors v. HHS), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s effort to force the American workforce to get Covid-19 vaccines (or comply with a strict test-and-mask regiment) (NFIB v. OSHA), and the Department of Education’s attempt to implement a sweeping “emergency” (yet post-pandemic) federal student-loan forgiveness program (Biden v. Nebraska).

“It is in this light,” I write, “that we should understand the government’s latest drive to take control of the Internet.”

I follow the guidance set forth by Justice Gorsuch, in a concurring opinion in West Virginia, on how to determine whether a major question is present. As Gorsuch’s review of the case law shows, an agency is dealing with a major question when it seeks to resolve an issue of great political or economic significance. And as I explain, that’s exactly what we have here. The new net neutrality plan is the latest chapter in a lengthy, contentious debate over a regulatory scheme that would alter prices, and suppress investment, in a many-billion dollar industry. More on that in the piece.

Here are two additional signs of major-ness that I didn’t cover in City Journal. First, the FCC is trying to short-circuit the legislative process. The “Court has found it telling,” Gorsuch observed in West Virginia, “when Congress has considered and rejected bills authorizing something akin to the agency’s course of action.” Congress has considered, but failed to pass, at least a dozen bills pitching Internet common-carrier rules.

Second, the FCC is trying to use an uncontroversial law to ram through a controversial policy. Writing for the Court in Nebraska v. Biden, Chief Justice Roberts remarked the “stark contrast” between the “sharp debates” around the Biden administration’s student loan-forgiveness program and the “unanimity with which Congress passed” the law that served as the program’s statutory hook. A similar dynamic is at play here. The current debate hinges on whether broadband is a Title I information service, or instead a Title II telecommunications service (and thus subject to common-carrier rules), under the Telecommunications Act of 1996. That statute passed the House by a vote of 414-16, and the Senate by a vote of 91-5. The dispute over where broadband fits in that statutory scheme, by contrast, has been marked by vicious arguments (even threats of violence), strict party-line votes, and seemingly endless rounds of litigation.

So the new net neutrality plan is a major policy decision. And the FCC lacks clear congressional authority to move forward with it. Back to the article:

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 is a deregulatory statute. In that spirit, it left the then-nascent Internet alone. “It is the policy of the United States,” it declares, “to preserve the vibrant and competitive free market that presently exists for the Internet . . . , unfettered by Federal or State regulation.” The FCC adhered to this statutory directive until 2015, when it reversed course and [imposed common-carrier rules in] the Open Internet Order. Even then, however, the agency acknowledged that the Telecommunications Act is, at most, ambiguous on the question of broadband’s regulatory status (Title I or Title II). . . . Statutory ambiguity is the opposite of clear congressional permission to resolve a major question.

As if that weren’t enough, I go on, the “Supreme Court has already concluded that, when it comes to the Internet, the Title I/Title II distinction is ambiguous.” In NCTA v. Brand X Internet Services (2005), the Court considered whether the FCC could place cable-modem Internet under Title I. Justice Thomas authored Brand X, and he has since repudiated it—for an informative reason. Brand X bows to the FCC’s reading of the statute—it grants the agency so-called Chevron deference. Thomas has come to believe that Chevron v. NRDC (1984) was wrongly decided. (He is not alone; the Court appears poised to overturn Chevron later this term.) Be that as it may, the crux of the Chevron rule is that a court defers to an agency when the underlying statute is unclear. Brand X found that the definition of “telecommunications service” is unclear, deferred to the FCC, and thereby established that Congress has not clearly permitted the FCC to regulate broadband as a telecommunications service under Title II.

Here’s a further point that’s not in the piece. It involves the FCC’s “forbearance” power. The utility-style rules in Title II pre-existed the Telecommunications Act of 1996. They were the rules that governed AT&T’s telephone monopoly in the mid-twentieth century. Many of them—especially the tariff rules, which required AT&T to file its rates with the FCC for approval—are wildly obsolete. In line with its goal of deregulation, the Telecommunications Act permits the FCC to “forbear” from imposing all the Title II rules on a Title II service. “Logically,” in the words of Judge Janice Rogers Brown, “forbearance is a tool for lessening common carrier regulation, not expanding it.”

That didn’t stop the Obama FCC from trying to use forbearance to hike up broadband’s regulatory status. When it shifted broadband to Title II in 2015, the agency elected to forbear from imposing 27 Title II provisions. It called this “Title II tailored for the 21st century”—“tailored,” here, being a euphemism for “rewritten.” The Biden FCC wants to pull the same move this time around, imposing burdensome common-carrier rules while also adopting “broad forbearance” for things like tariffs. Granted, the forbearance power appears in the statute. But the way the FCC wants to use it—as a regulatory ratchet and a red sharpie—confirms that the agency is applying the Telecommunications Act in a manner not clearly intended by Congress.

Check out the full article. The subhead reads: “The FCC’s ‘net neutrality’ push is misguided, but it looks certain to flunk the Supreme Court’s major-questions test.” That sums things up nicely.

2. Remarkably, the net neutrality plan seems rather modest, next to the FCC’s other new initiative. Let’s turn to City Journal article number two, “The Elephant in the Ethernet Port”:

Enacted in late 2021, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act runs more than a thousand pages. The table of contents starts off tolerably enough: early headings include “Bridge investment” and “National highway performance program.” Scan down, though, and you can practically watch the legislators lose focus. Before long they drift into “Sport fish restoration,” “Best practices for battery recycling,” and “Limousine compliance with federal safety standards.” But don’t nod off. On page 10, you’ll abruptly stumble on “Broadband.” (If you hit “Indian water rights settlement completion fund” or “Bioproduct pilot program,” you’ve gone too far.) This rather cryptic caption refers to a segment that begins on page 754. Start reading there, and you’ll eventually arrive at the last section of Title V of Division F—Section 60506, to be precise, on pages 817 and 818—which contains about 300 words on “digital discrimination.”

Consistent with this obscure provenance, the digital-discrimination directive doesn’t do all that much. It says a firm can’t deliberately withhold equal access to broadband service from an area out of animus for people in a protected class, such as race or religion. It directs the FCC to enact rules to that effect.

The FCC issued its digital-equity plan a couple weeks ago. Instead of following the statute, the agency asserts the power to control prices, mandate buildouts (even at a loss), oversee marketing and customer service, and more. Further, the agency wants to use this power to combat statistical disparities unrelated to discriminatory intent.

Article number two came out last summer. It, too, has a good subhead: “Progressives attempt to exploit a statute to facilitate a government takeover of the broadband industry.” My focus was indeed on what activists were pushing the FCC to do. I worried, at the time, that I might be nut-picking—devoting too much attention to comments submitted by the most radical progressive groups. Yet the agency has now picked up and run with almost every wild idea I discussed.

The FCC has thrown caution to the wind. The digital-equity plan “would,” Commissioner Brendan Carr warns, “give the [agency] a roving mandate to micromanage nearly every aspect of how the Internet functions.” As I noted last summer, though, this approach runs into—the major-questions rule:

Can a small provision buried deep in a thousand-page law revolutionize an entire industry? The answer, the Supreme Court has said with increasing clarity, is no. It is by now a cliché, among lawyers, that Congress should not be assumed to hide elephants in mouseholes. The line comes from an opinion authored by Justice Antonin Scalia in 2001, and it stands for the proposition that big, bold policy decisions require big, bold legislative statements. The Court recently formalized this principle, known as the “major questions” rule, in West Virginia v. EPA (2022), which tells Congress that it may not convey “extraordinary grants of regulatory authority” through “modest words, vague terms, or subtle devices.”

So the FCC might have not one but two major-questions smackdowns coming its way.

Read article number two, too. It remains relevant, given the FCC’s choice to let activists lead it around by the nose.

In the Supreme Court’s recent major-questions cases, the Court’s liberal wing has complained that the Court is seizing power from the executive branch. In reality, the majority has responded, the Court is checking increasingly brazen efforts by the executive branch to seize power from Congress. Is it any wonder that federal agencies cannot use creative readings of laws that are old, opaque, or both to declare rent holidays, make vaccines (nearly) a condition of employment, or forgive hundreds of billions of dollars in student debt? Or . . . turn broadband into a utility?

A Thankfully Doomed Mistake, City Journal (Nov. 2023).

The Elephant in the Ethernet Port, City Journal (June 2023).